THE ESSENCE OF COPENHAGEN SUMMIT: THE ‘GREEN OLD DEAL’

Alan Oxley , Copenhagen

The climate change negotiations in Copenhagen were thrown into chaos on Monday over a sticking point that will not go away: Money.

The UN suggested a fund of US$10 billion annually will be adequate. Later in the week Gordon Brown and Nikolas Sarkozy pledged $3.5 billion. The proposals were understandably ridiculed by developing countries.

Just two years ago the widely read Stern Report clearly stated that $160 billion was required annually.

Failure to do so, Stern suggested, would result in higher costs to future generations.

The current pledges are dwarfed by the amounts promised by the world’s development agencies and environmental campaigners within the past 12 months.

So where has all the money gone?

The unreality of the prospective windfalls to countries like Indonesia, which would be paid to curb emissions from forests or fossil fuels, has been replaced by international political and economic reality: rich countries cannot afford to subsidize development, no matter the cause.

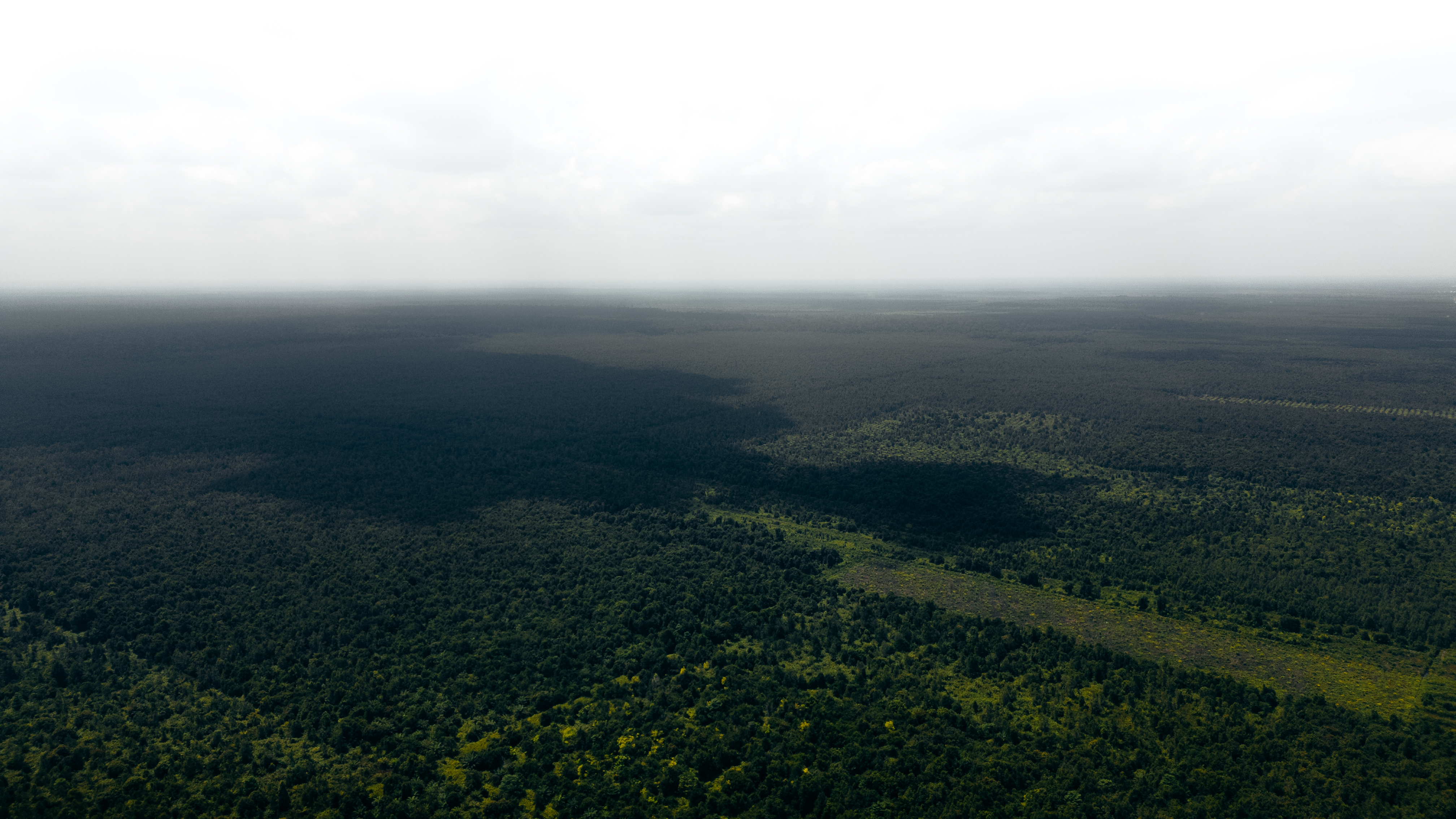

The clearest case in point – and the one that most affects Indonesia – is REDD. Familiar parlance among UN bureaucrats and environmentalists, it simply means payments for not cutting down forests.

An established carbon price in rich countries under a mandatory emissions trading scheme would instantly make conserved forests a saleable asset. International emissions trading has failed to materialize. Voluntary carbon prices have collapsed. Establishing and monitoring the amount of carbon in a forest has proven to be more difficult and expensive than first thought.

But above all, policymakers have finally realized that the reasons people cut down forests is to grow crops, procure fuel or secure land for housing. More advanced economies do so to create exports from crops or plantation forests.

The idea, then, of a market based mechanism for developing countries has been replaced by a ‘fund-based’ approach. In short, it’s aid for conservation.

Environmental campaigners such as WWF and Greenpeace have pinned their hopes on this model. Yet their priorities are ecologic rather than economic. At the end of the day they are environmental organizations; if curbs in economic growth support their long-term conservation objectives they will hardly object. Worse still, they have cynically enlisted the support of small vocal minorities, creating the perception that the poor world cares just as much about conserving forests as access to jobs, adequate healthcare or running water.

In truth, the only development model that exists in which the environment is preserved is the one undertaken by the US in the 18th and 19th centuries and to a lesser extent Europe from the 14th century onwards.

Simply, people will only start caring for the environment once basic needs – shelter, food, health and education – are met. This is certainly the case for Indonesia’s 40 million people living under the poverty line.

Aid agencies have had limited success delivering successful outcomes for basic needs – why should poor countries think they will deliver on something as complex as climate change or as untested as ‘low carbon development’?

The answer is to let poor countries forge a conventional development path. Natural forests might be reduced, ecosystems might be altered. But the key difference between contemporary Indonesia and 18th century America is that Indonesia has reserved last tracts of forest land for conservation.

Environmental assessments are mandated by law for forestry operations. Populations of endangered species are now being managed under active conservation programs.

The types of activities required for large-scale conservation have high costs that poor countries are understandably reluctant to meet.

Many existing conservation areas in Indonesia are rife with problems. One conservation group noted that national park enforcement staff in Riau were engaged in illegal logging. WWF officials in Riau were attacked by local communities for denying them access to forest areas.

Rather than making sure existing conservation areas work and removing the biggest incentive for deforestation – poverty – rich countries and environmental campaigners are instead telling small countries to create even larger conservation areas, which, in all likelihood will be poorly funded and at odds with the needs of local communities.

Three decades ago, the World Bank endorsed an Indonesian development strategy that condoned the expansion of plantations for the pulp and palm oil sectors. Both sectors have since made significant contributions to poverty alleviation in the ASEAN region.

Last month the Bank’s private sector arm suspended all funding for new palm oil developments at the behest of a well-funded environmental campaign group.

The Bank may think that sacrificing economic growth to keep groups like Greenpeace onside is fine. But poverty has not gone away. It is unlikely to unless the Bank and the rich world change tack and prioritize growth as a means to good environmental management – and a solution to climate change.

Otherwise, neither will be achieved.

The writer is chair of Washington-based NGO World Growth and the APEC Study Centre in Melbourne. He is currently in Copenhagen for the UNFCCC negotiations.