SATELLITE TECHNOLOGY TO PROTECT MARINE ANIMALS

By: Creusa Hitipeuw

Technological advances are apparently not only addressing human daily needs, but also helping conservation workers and institutions in protecting the wildlife. Monitoring technology through satellite is appropriately used to monitor the movement of migrating animals, for land animals and especially marine animals which movements are difficult to observe from the surface.

WWF-Indonesia Marine Program is currently using the monitoring technology through satellite tagging for three flagship species: turtles, whale sharks and tuna fishes; they are the flagship species of the Bird’s Head area of Papua, Teluk Cenderawasih, and of the Indonesian fisheries in general.

Data generated from the satellite monitoring provide more complete picture of the species themselves and also give important information for the habitat and location of the crossing and stopovers of those species; the disclosure of the location and the path will surely present information for the preparation of the conservation work strategy, including for the management of conservation areas or protected areas.

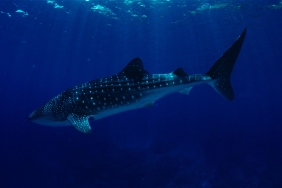

Example of whale shark migrating path after been scanned for two weeks. © WWF-Indonesia

The monitoring through satellite is not new; it is a method commonly used by the world researchers and scientists to collect data; for example, the satellite monitoring for giant white sharks to detect their movement in order to mitigate the potential conflicts with human.

Stalking the Marine Envoy

Indonesia has six out of seven of the world’s turtle species, including the largest and rarest species, leatherbacks (Dermocelys coriacea). Turtles can be found in almost all Indonesian waters, as well as the egg nesting location. With satellite monitoring, the WWF scientists know the migration routes, movement patterns and habitats important to sea turtles.

One of the satellite tag type before installment. © WWF-Indonesia / Natalie J TANGKEPAYUNG

Leatherback turtle running its path after the tagging installation finish, it will provide precious data about their life cycle. © WWF-Indonesia / Natalie J TANGKEPAYUNG

WWF conducts the satellite monitoring for leatherback turtles laying eggs on the Jamursbamedi beach, green turtles laying eggs in Derawan islands, olive ridley turtles on the Alas Purwo beach and several other locations. The collected data show the connection between the waters of the Bird’s Head area of Papua and the waters of the southern of Papua in Kaimana, Aru Sea and the west coast of the United States. Also there is a connection between the waters of Derawan islands and Sulu Sea, Sulawesi Sea and the west coast of Kalimantan. Meanwhile, the south coast of East Java is linked by turtles with the west coast of Australia.

Swimming with Tame Giants

Satellite monitoring for whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) has just started in 2011 by the WWF scientists in collaboration with the TNTC Office and the community of Teluk Cenderawasih. The data collected is still a few, but when it is compared to the data from visual monitoring that has been done since a few years earlier, it shows that the entire TNTC area is an important habitat for whale sharks.

The tagging installation is performed using a sharp weapon stuck in a body part that does not harm the animal. © WWF-Indonesia / Kartika SUMOLANG

The tagging is installed properly and immediately sends important information. Within a certain period of time, the tag will automatically detach itself. © WWF-Indonesia / Kartika SUMOLANG

Whale sharks can be found in all Indonesian waters, but the accurate monitoring activities have successfully identified that Teluk Cenderawasih has the largest population of whale sharks and is an important habitat that should be protected and managed properly. Whale sharks are found in groups consisting of 3-6 individuals, generally in the transition season of monsoon winds from west to east and vice versa.

Data from the monitoring can be used by the tourism sector to help promote Teluk Cenderawasih area and offer the right attraction for visitors.

Following the Fast Swimmers

Indonesian waters are also an important habitat for tuna, fish of high economic value that gives great income for Indonesia’s foreign exchange. There are huge numbers of tuna fishermen in Indonesia, both traditional and industrial-scale fishermen with longline vessels and purse seine. The facts that the number of the catchments is decreasing and the area is getting further have encouraged WWF to monitor the behavior and habitat of tuna.

One of the tagging types for tuna, pop-up-tag type. The installed type is similar to the tagging for whale sharks (the above picture). © WWF-Indonesia / Sugiyanta

Another type of non-satellite tuna tagging. This type requires the fishes to be recaptured to acknowledge the origin of the tag © Christian Daniel

The satellite tagging is installed on the adult-size of yellow fin tuna (Thunnus albacares) caught in Wakatobi waters, Southeast Sulawesi, with the help of traditional fishermen who caught it with stretching rod (handline). The installation of the transmitter is done by the WWF scientists, experts of marine species and the Office of Wakatobi National Park.

The collected data will indicate the migration patterns of tuna and other important ecological habitats such as the hatchery zone. With this knowledge, conservation efforts can be focused on habitats that have important ecological value, thus guarding the population of tuna in order to meet the consumption needs can take place effectively and efficiently.

The Use of Monitoring Data

Data collected from regular monitoring is very useful for various things. Knowing the movement of animals with satellite monitoring has proved to provide significant input to area managers to help determine appropriate strategies to reduce threats to the population and avoid conflicts between wildlife and human.

Based on the results of satellite monitoring in turtles, it is known that the turtle’s migration path has crossed with the fishing path, so a big number of turtles are threatened to be caught in fishing gear. The information states that turtle conservation efforts by just protecting the nesting sites is not enough, it also requires to protect the migration path. This encourages WWF to work with tuna fishermen and companies operating in Indian Ocean and Western Pacific Ocean. Similar to migrating tuna and whale sharks, oftentimes the threats come not only in the breeding habitat, but also in their migration path. The threats are usually fishing activities that are not environmentally friendly and destructive, as well as the traffic of large-scale transport and the development of marine and coastal areas.

The Facts about Satellite Monitoring Technology

- Monitoring tools: satellite monitoring using a transmitter attached to animals, which will send data to the satellite. The transmitter uses a battery that lasts for a period of time (usually in a matter of months or years) and can be switched off at any time if the monitoring is considered complete. The transmitter is attached to the animal’s body without hurting the animal and will detach itself after a certain period of time which is different in each species.

- Data generated: the transmitter attached to the animals records information on geographic location, water temperature, depth, salinity and various other information depending on the ability of these tags. Usually the more features it offers, the more expensive the price of the tags.

- Data processing: data from the satellite is transmitted to earth station that is run by the NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – an agency in the United States of America that deals with marine and atmospheric affairs)

- Costs and investments: satellite technology investment is very expensive for the moment; however, the information obtained is far more valuable than the investment. WWF-Indonesia believes that the use of satellites can help human life that depends on the balance of the ecosystem. Information to the fishermen of the general public should be spread so that if one day people find the satellite tags by chance, they can return it based on the identity printed on the tagging unit.

Contact: Creusa Hitipeuw, Marine Species Coordinator, WWF-Indonesia, chitipeuw@wwf.or.id

Notes:

- Whaleshark tagging: This study is in collaboration with HUBBS- Sea world Research Institute-San Diego, USA with support from WWF-Denmark and tag donation from Conservation International.

- Turtle tagging in Papua: Precious supports from NOAA, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, and from Packard

- Turtle tagging in Berau, East Kalimantan, and East Java: Supported by WWF-Denmark

- Tuna tagging: A comprehensive collaboration between Ocean Project, WWF-CTNI, WWF-Germany, and EDEKA